Not Every Beer That’s A Hit Is Worth Repeating

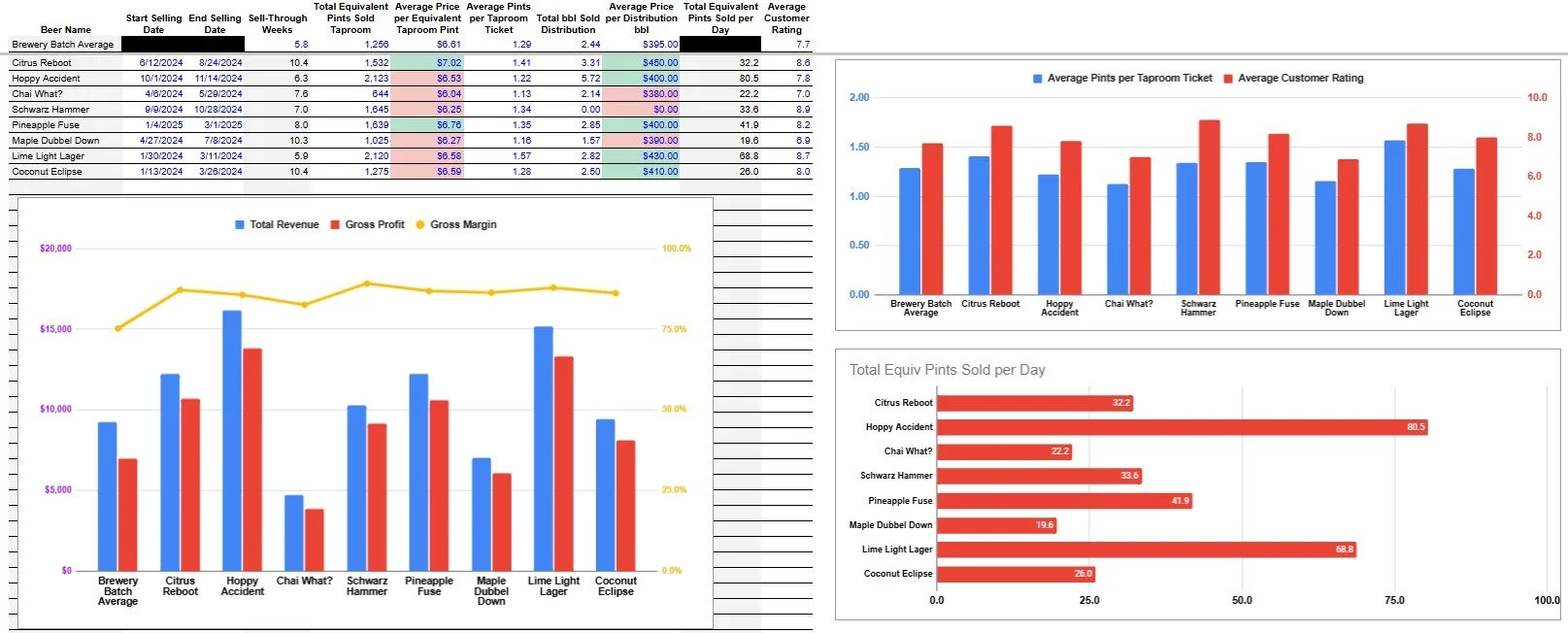

Beers that customers love aren’t always profitable. Don’t rely solely on customer feedback to decide whether a one-off, small-batch beer deserves a comeback. Use hard data to check your emotions (and your customers’) before committing valuable resources to experimental brews. Even if something sells fast, low margins can still make it a bad bet. Use tools like the Experimental Beer Postmortem to compare each release to your benchmarks before scaling up.

High ratings don’t mean high return on investment

High customer ratings don’t guarantee a good return on investment. In fact, ratings can be just as unreliable as focus groups and surveys. When you’re brewing an experimental beer, use customer feedback as a tiebreaker - not the main reason to rebrew.

Sometimes a high rating is just the result of novelty. Once the hype fades, customers may go back to their regular favorites. That’s why you need to look at hard numbers. Things like gross margin, sell-through time, and pints per ticket before deciding to bring a beer back.

Some brewers lean all the way into experimentation. They might have only two flagships, and everything else rotates. That model isn’t for everyone, but it’s built around one clear principle: don’t let beer sit. Sell it though.

Margin, sell-through, and what matters most

Rebrew decisions should start with gross margin. If a small batch isn’t hitting your benchmarks, scaling it up will only drag your business down.

What are your benchmarks? That’s up to you. I suggest using the average margin across your other beers. Perhaps giving your flagships a little extra weighting.

A 30% gross margin is a good minimum. Anything below that, and it doesn’t matter how fast it sells because there’s no room for error. One surprise in ingredients, labor, or overhead, and you’re underwater.

Also look at your sell-through window. If it takes more than six weeks to move a batch, your supply is outpacing demand. That ties up inventory space and increases your risk of spoilage. Tanks and taps are tied up rather than being used for faster-moving, higher-margin beers.

Another key metric: revenue per bbl. If demand is strong, pricing should reflect that. Here are some benchmarks to consider:

$1,000+ per bbl = strong

$750–999 per bbl = borderline

Under $750 per bbl = red flag

That applies whether you're selling in the taproom or wholesale. But let’s be real: wholesale volume for experimental beer is usually low, and the margin hit is steep.

Use the Experimental Beer Postmortem worksheet to track all of this - not just for your current release, but across every experimental batch you’ve brewed.

What to check before brewing that experimental beer again

Margin is your first filter. Sell-through window is second. Revenue per bbl is third. If you’re still on the fence, customer feedback can be a useful tiebreaker.

Want something more objective? Check average pints per ticket. If people really liked it, they didn’t stop at one pour. They came back for more.

If the numbers all look good, and customers love it, then sure, go ahead and scale up. If not, tweak the recipe or the pricing before you consider a full rebrew.